A former member of the El Salvador military involved in the most gruesome massacre in contemporary Latin American history has been detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Scripps News has learned exclusively.

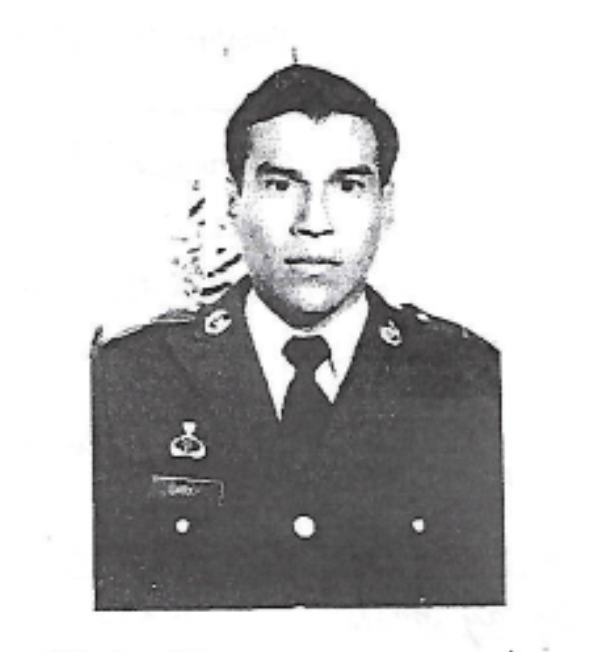

Roberto Antonio Garay Saravia — who served as a second lieutenant at the time of the 1981 El Mozote massacre — was arrested Tuesday following an investigation by HSI’s Human Rights Violators & War Crimes Center (HRVWCC), which obtained evidence related to the human rights violations.

"Individuals involved in heinous actions such as extrajudicial killings will not be permitted to remain here," said John Tsoukaris, director of ICE's Enforcement and Removal Operations field office in Newark, New Jersey. "We will maintain the integrity of our immigration laws and arrest those who violate them."

The El Mozote massacre is one of the most widely known killings in the history of the Americas, leaving between 800 and 1,000 civilians, mostly women and children, dead. It took place over three days in December of 1981, near the start of the bloody civil war that lasted until 1992.

"We don't know how many people were ultimately killed, but do estimate 1,000, with 553 were children and young people," said Terry Karl, a professor of political science at Stanford and director for Latin American studies who has worked as a war crimes investigator. "During one excavation site, they found 143 people, of which 131 were children whose average age was six."

Garay Saravia was later promoted and ended his career as a colonel in the Salvadoran armed forces.

Due to an amnesty law that went into effect in 1993, no one was prosecuted following the murders, even as a peace agreement went into effect the year prior, which set up a truth commission and allowed the exhumation of human remains from the massacre.

"Both the United States and the Salvadoran government and military denied (at the time) that there had been a massacre," said Karl. "They absolutely denied it. And they denied it all the way up to the forensic digs in the early '90s. It was only the discovery of these little tiny skeletons. That meant that you had to admit that something really terrible had happened in this town."

At the time of the brutal attacks, the U.S. had not only been sending military aid to El Salvador to the tune of $1 million per day (nearly $1 billion over that decade), it had also supported and trained the combat unit involved, which it continued to do after the massacre.

"When this massacre happened over 40 years ago, the U.S. was aggressively supporting the military, and at least one senior intelligence official was at or close to the scene when the massacre was carried out," Geoff Thale, former director of the Washington Office on Latin America and an expert on El Salvador, told Scripps News. "The American public didn’t want another ugly war that we were supporting war crimes in and human rights abusers," he said. "It’s important the truth about this comes out, because we need to learn ... and reexamine our own history."

That amnesty agreement was not lifted until 2016 by the Salvadoran Supreme Court, which then allowed for an investigation and charges to be brought against those involved.

According to ICE, Garay Saravia was admitted legally by U.S. Customs and Border Protection into the U.S. in March of 2014.

It wasn’t until 2017 that he was charged in relation to El Mozote in El Salvador, as they brought charges against at least 18 military officers involved; it is unclear whether those charges were only brought as part of the investigation in El Salvador or also by the U.S. government.

In August of 2019, a Salvadoran judge also charged him with war crimes and crimes against humanity under the international Geneva accord. According to ICE, Garay Saravia was also deployed in massacres in the department of Cabañas, and at La Quesera and El Calabozo, which resulted in the killing of hundreds of noncombatant civilians.

He will be prosecuted by Newark and Philadelphia immigration courts.

"We owe these people who died and their family members the truth; we owe it to them as the United States, not just as El Salvador, because we, the U.S. government, helped to cover up this crime," Karl said. "This is one of the worst massacres in the history of Latin America. And somebody has to be accountable in some way ... the dead deserve justice just as much as people who are alive and dead have rights too, and when you see the skeletons of small children, you know that they deserve — and we all deserve — to know who did this."